Summer in Santa Fe: Lowriders cruise the Plaza, Farmers’ Market people-watching is at its peak and restaurant patios overflow with margarita-sipping tourists. It’s a heady time of year, with a veritable carousel of art openings, fairs and fests; here are some we try not to miss. Grab a highlighter, mark your favorites, and stick it on the fridge.

Canyon Road Summer Art Walk

5-8 pm first Wednesdays June–September. Free Canyon Road, canyonroadsummerwalk.com

If checking out Canyon Road on a weekday night hasn’t always been a summertime must-do—same. But last summer’s popular Canyon Road Summer Walk series, which saw galleries and other businesses open their doors not just to art buyers but to curious locals, is back, and replete with artist demos, live music, and all kinds of other fun stuff like pop-up churro bars and after-dark theatrical performances.

2. CURRENTS New Media Festival

Opening Day: 5-10 pm Friday, June 13, then daily through Sunday, June 22

$10–$15; kids under 10 free. El Museo Cultural de Santa Fe, 555 Camino de la Familia, currentsnewmedia.org

CURRENTS New Media Festival will return to its original digs in the Railyard this year, taking over El Museo Cultural for 10 days of immersive digital art experiences that explore the ever-changing interaction of tech and human touch. International exhibitors at the top of their fields—be it animation, VR, AR, and other digitally driven art disciplines—invite visitors to engage, explore and have a complete blast.

3. Native Dance Series presented by Museum of Indian Arts & Culture

Various times, Saturday, June 21; Saturday, July 19; August 2–3. Free. Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, 710 Camino Lejo, indianartsandculture.org

If you’re planning a trip to Museum Hill this summer, consider timing your visit to catch one of three performances from MIAC’s Native Dance Series. Against the mountainous open-air backdrop of Museum Hill’s Milner Plaza, you’ll see Puebloan dance troupes from Albuquerque, Ohkay Owingeh and beyond sharing centuries-old dance traditions resplendent with pride and spirituality.

4. Santa Fe Pride on the Plaza

9 am-5 pm Saturday, June 28. Free. 63 Lincoln Ave. hrasantafe.org/pride-2025

Blossoming apricot trees, thrumming insects and penetrating cerulean skies? Summer in Santa Fe is downright sensuous. Celebrate love’s abundance in every vibrant shade of the rainbow at Santa Fe’s 32nd annual Pride on the Plaza from the Human Rights Alliance Santa Fe. There’s a parade, live music, drag performances and community booths on June 28, but all sorts of other events like Queer Prom Night, Madrid’s funky and fabulous Pride Parade and Pride After Dark to keep the party going all month long.

5. Rodeo de Santa Fe

5 pm Wednesday, June 18 through Saturday, June 21. $10-$25. 3237 rodeo Road, rodeodesantafe.com

Mustachioed cowboys, boot-scootin music and American prairie-core aesthetics are everywhere right now, so why not embrace it? Throw on your bolo tie and check out our town’s annual Rodeo de Santa Fe, where the energy is electric, the outfits are iconic and the people-watching alone is worth the price of admission. In the arena, catch bull riders and barrel racing, then peep the vendor area for games, beer and classic fair treats.

6. Santa Fe Opera

Various times and shows Friday, June 27 through Saturday, Aug 23. $48-$264. 301 Opera Drive santafeopera.org

Heartache, forbidden love and cosmic destiny are all part of the juicy drama unfolding nightly at this summer’s 68th annual Santa Fe Opera. This season’s five rotating productions—La Bohème, The Marriage of Figaro, Die Walküre, Rigoletto, and The Turn of the Screw—offer timeless stories told with world-class voices and state-of-the-art set design. Opera aficionados can catch pre-show lectures, apprentice nights, and chic-but-laid-back tailgating.

7. Pancakes on the Plaza

7 am-5 pm Friday, July 4. $8-$10. 63 Lincoln Ave. pancakesontheplaza.com

Independence Day celebrations begin at 7am, when volunteers spread out across the Plaza and flip pancakes for patriotic—or just hungry—visitors. After breakfast, stroll the tree-lined Plaza to admire vintage cars and browse handmade goods from local artisans. Best of all, this syrupy carb fest supports do-good youth programs like YouthWorks! and the Children’s Museum.

8. Santa Fe Wine Festival

Noon-6pm Saturday, July 5 and Sunday, July 6

$10-$80. 334 Los Pinos Road, golondrinas.org

Do you get a kick out of Southwestern history, regional wine tasting or both? The Santa Fe Wine Festival, now celebrating its 31st year at living history museum El Rancho de las Golondrinas, is for you. Here, local vintners invite you to sample wine, and you can browse handmade crafts, and grab bites from beloved regional vendors. Carve out some time to break from the crowds and meander around the enchantingly rustic, cottonwood-shaded grounds.

9. International Folk Art Market

All Day Friday, July 11 through Sunday, July 13

Free-$311.52. 740 Cerrillos Road, folkartmarket.org

Santa Fe’s annual International Folk Art Market, hosted in the Railyard Park, is the world’s largest fair of its kind. Around 150 craftspeople from 50 countries make the trek to Santa Fe each July, where they sell handmade goods and share creative practices. Where else can you meet weavers from Peru, basket-makers from Rwanda and silversmiths from Uzbekistan? Music, art demos, delicious food, and connecting with world-wide creatives await.

10. Traditional Spanish Market

8 am-5 pm Saturday, July 26 and Sunday, July 27. Free. traditionalspanishmarket.org

Each summer, The Atrisco Heritage Foundation’s Spanish Market transforms the Plaza into a celebration of Northern New Mexican art traditions, many of which have been lovingly practiced here for centuries. You’ll find plenty of devotional art, much of it emphasizing beloved regional Catholic saints, as well as weavings, tinwork and silver jewelry. Steps from the main show, check out the Contemporary Hispanic Market, which hosts established and emerging Latino artists.

11. Santa Fe Beer & Food Festival

Noon-6 pm Saturday, August 9 and Sunday, August 6. $8; kids 12 and under free

334 Los Pinos Road, golondrinas.org

New Mexico’s food culture is the stuff of legends, but we also enjoy a truly impressive regional brewing scene. Check out some of the friendliest vendors around at the Santa Fe Beer & Food Festival at El Rancho de las Golondrinas. Sip craft beers made with locally grown hops, savor dishes from regional food vendors and enjoy live music, artisan markets and hop-harvesting demos, all on the stunning, historic grounds of a centuries-old ranch.

12. Santa Fe Reporter’s Best of Santa Fe Party

Each year, Santa Feans cast thousands of votes for our favorite local businesses, service providers, and personalities. Once the results are in, the Santa Fe Reporter’s Best of Santa Fe Bash throws a big, free block party to celebrate the winners and the community that loves them. Meet the folks behind your favorite spots, grab some great food, and enjoy live music [BAND?], drinks, and local flair.

13. Pathways Indigenous Arts Festival

All Day Friday, Aug. 15-Sunday, Aug. 17. Free. poehcenter.org/pathways

Hosted by the Poeh Cultural Center, the now-annual Pathways Indigenous Arts Festival at Pojoaque’s Buffalo Thunder Resort Casino is well worth the 15-minute drive from downtown Santa Fe. The show is run by and for Indigenous artists, and you’ll find over 300 of them in a relaxed, come-one-come-all vibe. Think of Pathways as a chilled-out version of Indian Market, and browse paintings, pottery, jewelry and more without having to elbow your way through the Plaza.

14. Santa Fe Indian Market hosted by the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA)

8 am-5 pm Saturday, Aug 16 and Sunday, Aug 17 Free. Santa Fe Plaza, 63 Lincoln Ave.,swaia.org

For over 100 years, the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts’ Santa Fe Indian Market has transformed the Plaza into the nation’s largest and best-known Indigenous art fair. With 1,000 top-tier Native artists representing more than 200 tribes, plus food vendors, dance performances, film screenings and evening galas, the event is a can’t-miss, vibrant celebration of Indigenous creativity and culture.

15. 101st Burning of Zozobra

Friday, Aug. 29. $30-$374.99; kids 10 and under free. Fort Marcy Park, 490 Bishop’s Lodge Road burnzozobra.com

If you’ve ever stood in the crowd at Zozobra, cheering as a 50-foot puppet full of strangers’ regrets goes up in flames, you know it’s more than an impressive feat of pyrotechnics and crowd-management; it’s Santa Fe’s annual collective emotional exorcism. Old Man Gloom moans, flails, and burns, taking our bad vibes with him in a blaze of fire and fireworks. This year, the theme is steampunk, so consider casting off your gloom in goggles and a jaunty tophat.

By Iris Fitzpatrick // May 21, 2025

Iris Fitzpatrick // May 2025

From Mexico, With Love

by Iris Fitzpatrick // February 5, 2025

Chef Eduardo Rodriguez at Zacatlan. (photo Iris Fitzpatrick)

It’s late morning, and Eduardo Rodriguez and I are sharing a booth in a sun-splashed corner of Zacatlán (317 Aztec St., (505) 780-5174), his Mexican-Southwestern restaurant on Aztec Street in Santa Fe.

The chef and restaurateur tells me his hometown, the central Mexican city of Zacatecas, isn’t all that different from Santa Fe. The streets in both, he says, are narrow and winding, lined with pinkish-orange buildings that acquire an enchanting glow just before nightfall. In Zacatecas, just like in Santa Fe, chile peppers reign supreme, and grow happily in the arid, high-altitude countryside.

“People in Zacatecas feel a kinship with Santa Fe,” Rodriguez says. “We understand each other.”

He is patient and poised, but also excited having recently returned from a trip to Mexico, from which his mind is swimming with new culinary ideas.

“I tried an amazing miel de maguey (agave syrup) in Oaxaca,” he says, eyes sparkling. “You don’t see it used much here, and I can’t wait to experiment with it.”

Rodriguez has always felt comfortable in the kitchen. He remembers watching his abuela stirring gigantic pots of mole, adding this and that, letting things simmer low and slow.

“Growing up in a big family,” he says, “there was always an important meal to cook because there was always something or someone to celebrate.”

When Rodriguez moved to Santa Fe as a teenager in 1994, he was following in the footsteps of his two big brothers, Jose and Juan, who worked in the kitchen of Coyote Café.

“There was so much energy there,” Rodriguez says. “The food was exciting and different, and people were calling [Coyoté Cafe chef] Mark Miller the padre of Southwestern cooking.”

Rodriguez got his start washing dishes at Geronimo, another then-new and buzzy restaurant, helmed by the late chef Eric DiStefano. Rodriguez worked hard, and DiStefano noticed. Within a few months, the young dishwasher was promoted to the line, cutting vegetables and filleting fish; by the end of his 13-year tenure at Geronimo, Rodriguez was DiStefano’s right-hand man. The two chefs moved from Geronimo to Coyote Café in 2008, working side by side until DiStefano died unexpectedly in 2016.

“There was chaos when Eric died,” Rodriguez recalls. “But I knew how to run the kitchen, so I stayed, and stepped into the position of executive chef.”

As time went by, Rodriguez found himself yearning to open a restaurant of his own.

“During my 13 years at Coyote Café and in the 13 years at Geronimo before that,” he explains, “lots of people believed in me and encouraged me to do my own thing.”

In response, Rodriguez opened Zacatlán in summer 2020.

“It was a risk, and I knew that,” he says of launching a restaurant during a pandemic, “but it was time for a change, and Zacatlán is my baby.”

This baby, now in its fifth year, has been a success. In 2021, Zacatlán was named one of the best new American restaurants by USA Today’s 10Best readers/experts poll. The next year, Zacatlán was a semifinalist for a James Beard Award in the Best New Restaurant category and, just last spring, Rodriguez nabbed a Beard nomination for Best Chef: Southwest.

Just like Santa Fe, Zacatecas was founded by treasure-seeking, 16th-century Spanish conquistadors who tried to make their new environs as European as possible. For centuries before the Spanish arrived, though, these places were traversed by groups of Indigenous people. They hunted rabbit and deer, and planted maize, beans and medicinal herbs. Relying on the land for sustenance engenders a lifelong reverence for it.

“My mother lives here in Santa Fe now,” Rodriguez says, “but grew up in Zacatecas. Whenever she’s outside, she still scans the ground for edible plants. She’ll point out things that other people don’t even notice, and says, ‘you can eat that,’ or ‘don’t eat that.’”

Rodriguez approaches cooking with the same passion for finding and sharing good things. Though he’s planning to tweak a couple menu items at Zacatlán, he knows better than to shake it up too much.

“I’m more interested in refining the recipes that people come here to eat,” he says, “not completely changing them.”

Rodriguez is always learning, and always innovating. During a trip to the Yucatán several years ago, he watched a man preparing ceviche with impressive speed.

“He filleted the fish beautifully,” he says, “but then discarded the carcass once he got the meat out.”

It didn’t sit right with Rodriguez.

“My abuela used all of the animal when she cooked, so that’s what I try to do,” he says.

At Zacatlán, for example, Rodriguez’s red snapper is shaped into a curved, canoe-like vessel—fins and all—lightly fried, then stuffed with crab and saffron risotto. Technique and creativity similarly shine in Rodriguez’s Robin Egg dessert, which comprises a Tiffany-blue, molded chocolate shell on a bed of crumbled biscochitos and chocolate mousse. Inside, a quivering, gelled mango “yolk” rests on puffy coconut cream “egg whites.” It’s over the top, and that’s how Rodriguez likes it.

“When you go to a vegan restaurant,” he says, “you don’t order a cheeseburger. When you come here, you don’t order food that you can easily cook at home.”

Korma Chameleon

Chef Paddy Rawal tried to retire, but Santa Fe won’t let him

December 4, 2024

The community’s obsession with Mumbai-born chef Paddy Rawal -began with Indian restaurant Raaga, which Rawal opened on Agua Fría Street within months of moving to Santa Fe back in 2011.

When he abruptly closed the wildly popular restaurant in 2017 due to stress-related medical issues, Rawal’s loyal fans weren’t just surprised, they were bereft. People in the community—friends, peers, total strangers—had no qualms asking him to return to the culinary scene, however, and in 2018, after taking time to travel, rest and reflect, Rawal opened Raaga-Go, a scaled-down, takeaway version of his popular eatery.

Then came 2020. Pandemic closures initially provided a boost to Raaga-Go’s delivery format, but when sit-down restaurants reopened, Rawal says, business faltered. He closed Raaga-Go in 2023 and immediately experienced deja vu.

“I kept bumping into people around town who said, ‘Paddy, we need you!,’ and ‘Paddy, where did you go?’” he tells SFR.

Once again, Rawal traveled, rested and reflected, and, like 2017, he decided he wasn’t done cooking in Santa Fe. Rawal, who has appeared on major cooking competition shows like Chopped and Beat Bobby Flay, knows he’s got star power and finesse, and calls himself “a known entity” around town. Six months after closing Raaga-Go, he began designing the menu for Tulsi (839 Paseo de Peralta, (505) 983-6927), his new Indian and Asian restaurant in downtown Santa Fe. Now he’s ready to pull the trigger.

I visit Rawal in late November, less than a week before Tulsi’s opening day. The walls of the restaurant, which previously hosted well-loved Mexican spot Mucho Gusto for 20 years, are still decorated with framed Diego Rivera prints and colorful Mexican baskets. Unopened boxes of kitchen equipment sit stacked to the ceiling, and huge stainless steel mixing bowls, still in their shrink-wrap, are nested haphazardly into each other. On a table, several dozen of Rawal’s cookbooks (he’s written two and is working on a third) form small towers. As the chef and I sit down to talk in the empty dining room, electricians and delivery drivers tramp in and out, and the phone rings frantically. Nevertheless, Rawal remains focused, energized and completely serene.

“If my cooking brings comfort and joy to people, then my life improves,” he says. “You could call it karma.”

Last spring, with the reluctant blessing of the same physician who told Rawal to step back from Raaga in 2017, the chef secured financial backing from a silent partner, developed a menu of Indian and Southeast Asian dishes and purchased the Mucho Gusto space from its chef-owner, his friend Alex Castro, who was looking to move on. Moving on, of course, has proven difficult for Rawal. Preparing food comes naturally, he says, adding that it might come from when he was growing up and would help his mother cook for their family of seven.

“My mother was a master of spices,” Rawal says, “but she used a light touch; she always said, ‘spice for flavor, not just for heat.’”

Rawal’s mother was also a Hindu priest, and performed puja, or holy rituals, for a range of auspicious occasions around town.

“My mother believed we must participate in life in order to get the most out of it,” Rawal notes, “and that stuck with me.”

At Tulsi, Rawal wants visitors to experience what he calls the “theater of Indian cooking,” with all of its attendant drama: richly layered flavors and piquant herbs and spices, of course, added with a delicate touch. Classics like chicken tikka masala (the same recipe Rawal used to beat Bobby Flay in 2020), saag paneer and samosas are complemented by Thai and Malay standbys like green curry, pad thai and tom yum soup. Many of Tulsi’s most frequently used ingredients—cumin, cilantro, tomato—are staples of both Indian and Southwestern cooking, so Rawal pays tribute to both. A crispy okra appetizer, for instance, is served with fresh pico de gallo, and ancho chile gives Tandoori chicken a smoky punch. Several dishes include the restaurant’s namesake, tulsi, or holy basil. According to Hindu tradition, this leafy herb with the licorice-clove kick is the earthly manifestation of the goddess Tulsi, a paragon of purity and devotion, and consort to Lord Vishnu.

“Tulsi is sacred in India,” Rawal explains, “and it’s used in Hindu ceremonies to bless something or make it sacred.”

In his younger days, Rawal studied Transcendental Meditation and Zen Buddhism, and attended ISKCon and Osho lectures. Even though he doesn’t think of himself as religious, per se, the concept of devotion is familiar and comforting to Rawal, whose mother recited Bhagavad Gita passages from memory every morning and made sure that all five of her kids said their prayers daily.

“I still spend a lot of time meditating and looking within,” Rawal says, “and I try to do as much good as I can.”

I visit the restaurant again, early on Thanksgiving Day, and powdered-sugar snow frosts the road. Rawal had been working in his new kitchen for hours, preparing a feast of turkey, gravy, sweet potatos—the works—for people he loves. Karma, for Rawal, is like cooking. Both rely on a strong, intuitive foundation that gets refreshed, and somehow blessed, with each mindful action.

Chef Paddy Rawal /photo Adam Ferguson

written by Iris Fitzpatrick / Nov 20, 2024 / photos by Steven St. John

William Goodman in his studio

I set out for Tinnie, a rural spot in the southeastern corner of Lincoln County, to meet sculptor, painter, and tinkerer, William Goodman, who recently celebrated his 87th birthday.

This part of the state is well-known for the bloody Lincoln County Wars, but the artist doesn’t ruminate much on this past, nor does he consider the local landscape to be a crucial facet of his art practice. "I don't consider my art to be overly concerned with my environment," Goodman told me from the dusty driveway of his rugged compound. "I get inspiration from doing things like visiting the dump."

From the “dump”—really just a row of trash cans on a lonesome stretch of highway—Goodman once salvaged an entire piano. "It was quite old, and beautifully made," he told me. Goodman dissected the piano, harvesting assorted doohickeys and thingamabobs to use in his wildly designed and hand-built pinball machines.

Enter William A. Goodman’s Creative World

In the far reaches of Lincoln County, octogenarian artist William A. Goodman continues to make wildly creative work on his own terms.

IF THE STATE of New Mexico is viewed as a torso, Lincoln County is its slightly east-of-center belly button. That core has a rich history. Centuries before New Mexico became a state in 1912, Lincoln County’s mountains, forests, and deserts were crossed by Mogollon, Piro, and Apache peoples. By the 1850s, Mexican families had set up communities along the area’s riverbanks. Lincoln County is now known for the 84-mile Billy the Kid National Scenic Byway, a much-visited stretch of US 70 where the brutal Lincoln County War took place in the late 19th century. Today, most of the drama in Lincoln County comes from its striking terrain.

Artist William A. Goodman lives in the southeastern corner of Lincoln County, in Tinnie. Roughly equidistant between Ruidoso to the west and Roswell to the east, Tinnie nestles in the pleasantly green Hondo Valley, near the intersection of US 70 and 380. Although Tinnie is tiny and remote, this part of Lincoln County is not entirely foreign to artists. To the west in San Patricio, painters Peter Hurd (1904–1984) and Henriette Wyeth (1907–1997) settled and raised a family. Even closer, in Hondo, lived sculptor Luis Jimenez (1940–2006), whose studio Goodman visited weekly for a Tuesday lunch date that lasted until Jimenez’s death.

In Tinnie, a smattering of buildings—Goodman’s 1880s-era home, a long-shuttered motel, and a former gas station and auto garage—comprise the artist’s property. Interspersed throughout the cacti-specked spread are a dozen or so of Goodman’s abstract steel sculptures, many more than 10 feet tall. On a late summer visit to Goodman’s compound, I park near the monumental Starling, whose ropy steel tendrils overlap to converge in a beaklike point. Up close, its thousands of tiny welds look like seams of a metallic patchwork quilt. I’ve come here to meet Goodman, an artist known for throwing himself into demanding disciplines—whether welding steel, stabilizing 20-foot-tall sculptures, troubleshooting analog arcade games, or painting outsize murals—with rigor and enthusiasm.

Lincoln County, with its terrain filled with dramatic starts and stops—and a past laden with outlaws—deserves an artist like Goodman, who does not sell his work through a gallery and does not have an agent. “When people want to buy something,” he says, “they usually just visit me.”

He turned 87 in October, continuing to make art proudly to the beat of his own drum, powered by seemingly bottomless energy reserves. Often called eccentric, Goodman is something of an elder statesman around these parts. As one of the first graduates of the Roswell Artist-in-Residence (RAiR) program in the late 1960s, he liked the area so much he stuck around. “William is always working and always has a project,” says Larry Bob Phillips, director of RAiR, who likes taking new resident artists to Goodman’s studio. “He doesn’t need external factors to drive his creativity.”

GOODMAN IS COMPACT AND QUICK AND speaks with the effortless animation of someone whose mind is always alight with ideas. While growing up during World War II in the affluent London suburb of Wimbledon, he remembers seeing bombs land on his town’s famous tennis courts, but he does not recall experiencing fear. “It’s just the way it was back then,” Goodman says. “War was normal to me.”

At 18, Goodman volunteered for the Royal Navy to avoid being drafted for military combat. “I was picked on mercilessly in the navy because I did not come from the working class,” he says. But there was a rum ration, unlimited cigarettes, and visits to far-flung locales like Oman and Sri Lanka. In 1959, Goodman moved permanently to America by way of San Francisco, selling crabs on Fisherman’s Wharf before he eventually wandered into the city’s California School of Fine Arts. He ended up falling in love with creative practices, leaving with degrees in both painting and sculpture. “I hadn’t planned on becoming an artist,” he says, “but my commitment to art was similar to my commitment to the navy. I didn’t look back.”

He arrived in Albuquerque in the late 1960s, initially for an art teaching position at the University of New Mexico, where he worked for several years before deciding a professor’s life wasn’t for him. When a friend told him about the Roswell Artist-in-Residence program, Goodman applied.

RAiR, now in its 57th year, was the brainchild of Don Anderson, an oilman and passionate self-taught artist. It led to such a prolific artistic output that the Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art was founded in 1994 to store and display alumni artwork. “When I first met Mr. Anderson, he bought a couple of sculptures from me,” Goodman recalls of his early patron. “Then he commissioned three more. It was a great boost.”

As its director, Phillips likens the experience of the residency to “the rarest gift of all, which is time,” he says. “The program has no strings attached. There are no expectations and no distractions.” Phillips, an accomplished muralist, applied for his own spot in RAiR’s program several times before he was accepted in 2009. In Roswell, he met Goodman and immediately recognized him as “an artist in the truest sense of the word.”

Tinnie is the perfect place for such a person: It’s remote without feeling desolate, soaked in a rugged history that Goodman respects and preserves in his studio. Twenty-five years after he moved into the former auto garage and parts shop, dust-covered inventory in its original packaging still fills the space, much of it neatly hanging on rusted display racks.

The old motel on Goodman’s property is on the rim of Tinnie Canyon, a perch that the artist tells me has been slowly eroding into the valley below for years. Thorny weeds and wispy grasses protrude from the pale earth. Animal bones adorn the uneven ground that leads up to the inn, which shuttered permanently many decades ago. Goodman has renovated three of its five narrow, cell-like rooms, where he stores personal items—a bedroll nudged close along a window, stacks of paperbacks—as well as works from his three-dimensional hanging Landmask series. The sculptures, whose molded-paper ridges and valleys are assembled atop wire armatures, contain rigidly angled areas and sometimes bubbling, bulbous forms which stop just short of resembling realistic environments.

The landform sculptures were inspired by Goodman’s time as a coal mine surveyor, a gig that took him away from New Mexico for four years in the 1970s. “I was trying to figure out how to get a bulldozer into a pit,” he explains. “The Landmasks were made to resolve it.” He lost the job before he could test their efficacy, but he continues to work on the series.

Goodman wakes just before midnight to jog several miles along NM 368, which runs through the center of his property. “It’s an uncommonly good place to run at night. The road is dirt but it’s well-maintained,” he says. “Everything is illuminated by a misty kind of starlight.” Back home, he breakfasts around 2 a.m. on oatmeal measured out from a 50-pound bag, then goes back to sleep before spending the day at work in his studio. Dinner is often rice and beans, also purchased in bulk; the hours between dinner and sleep are filled with reading.

“I like people, that’s the truth,” Goodman says, explaining his solitary lifestyle. “But making things engages me completely.”

He does not employ an assistant. “He’s so focused and has so much experience,” Phillips says, “that almost anybody is in his way.” Goodman’s longtime friend Miranda Howe agrees. “William is alone a lot, but he definitely has a social life,” she says. “People stop by his studio in Tinnie a couple times a week.”

Howe, a 2012 RAiR participant, is also a part-time employee at the Anderson Museum, where Goodman’s featured works include Artesian, a high-shine galvanized steel sculpture near the museum entrance, and Cascabel, a crank-operated percussive instrument of Goodman’s own invention. “The musical instrument is a great way for people to get to know William because it’s so imaginative,” Howe says. “People don’t walk into a museum expecting to be able to touch the art.”

Goodman calls Roswell, where he lived for many years before moving to Tinnie, “my home base.” He heads there to visit friends from RAiR and the Anderson and Roswell museums, both of which feature his monumental sculptures in outdoor spaces.

In 2021, the Roswell Museum mounted a retrospective for the artist that also served as an anniversary of Oddy Knocky, a 37-foot-long mural on canvas completed in 1971. Action-packed and wildly colorful, Oddy Knocky’s cast of characters includes a tugboat whose bow side looks an awful lot like a human face, a dragon playing a trumpet, a white cube sprouting twisty cables or veins, and a foot disappearing up the steps of a dark tower.

Goodman named the painting after a slang term invented by Anthony Burgess in A Clockwork Orange. “Oddy Knocky means ‘to be on one’s own,’ ” Goodman says. “I was alone making this, often teetering on top of a ladder with a paintbrush.”

Roswell Museum’s executive director Caroline Brooks says that among the many paintings in the museum’s collection, Oddy Knocky is a favorite of school groups and other museum visitors. “We love Oddy Knocky because of its inventive characters, all parading through such fantastical worlds,” she says. “There’s so much movement that one can’t help but imagine a racket of sounds."

THIS SENSE OF MOVEMENT UNDERSCORES much of Goodman’s work, from his paintings and Landmasks to his towering, amorphous sculptures. Several of the latter are scattered across the state, including on the grounds of New Mexico Highlands University in Las Vegas and at the federal plaza in Las Cruces.

Lately, Goodman has been engrossed in creating pinball machines and is working on his sixth. A pinball game Goodman made in 2016, Kinetic Park, is covered with the same precisely patched-together welds used on his monumental sculptures, its Lilliputian valleys a faded green. The game is populated with magnetic obstacles like wide discs, cone hats, and red-and-yellow flagpoles, all of which can be moved.

When it’s time for me to go, Goodman says goodbye near a 12-foot kinetic sculpture named Zephir. Its gnarled, three-pronged top is designed to rotate in the wind. Suddenly, Goodman’s head cocks to one side, alert to its creaking sound. “That sounds terrible,” he says. He smiles as he studies the steel structure before us. “Luckily, it’s easy to change the bearings on this one.”

Iris Fitzpatrick visited Lincoln County for the first time in August, where she fell in love with its varied landscapes and engaging, kind people.

William A. Goodman stands inside his converted-motel display space

"Oddy Knocky" is a favorite of school groups and other Roswell Museum visitors. Gift of Donald B. Anderson and Sally M. Anderson. Courtesy of the Roswell Museum

William A. Goodman with one of his pinball machines

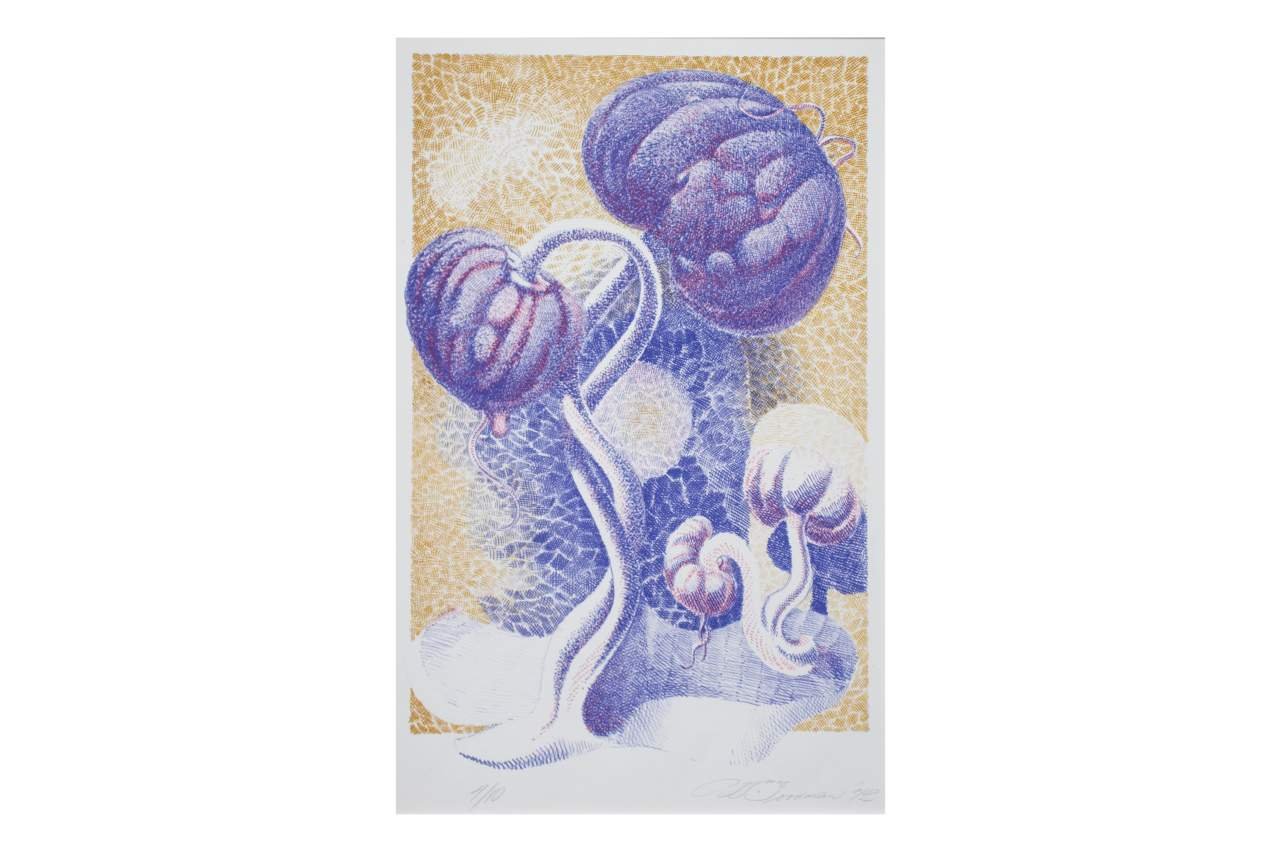

"Untitled," lithograph on paper. Courtesy of the Roswell Museum

The artist’s Gordian sculpture, in Tinnie.

Do Glaciers Dream of Melting Sheep?

Tristan Duke’s SITE Santa Fe show examines Earth’s fiery temperatures from an icy perspective

by Iris Fitzpatrick / October 23, 2024Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

In the poem above, Robert Frost imagines doomsday by assigning human traits of jealousy and passion, disinterest and hatred to seemingly opposing, non-sentient entities—fire and ice. Written in 1920, Frost’s poem predates the discovery of Antarctica’s Florida-sized Thwaites Glacier by several decades. Thwaites is called “Doomsday Glacier” because it’s melting at an alarmingly fast pace, shedding massive ice chunks into an ever-warming ocean. Within a couple hundred years, scientists say, Doomsday will melt entirely, causing disastrous changes to the world’s sea levels.

Glacial Optics, on view at SITE Santa Fe through March, features large-scale photographs by Los Angeles-based artist Tristan Duke. Duke’s previous works include holographic installations and handmade pinhole cameras; for this project, he replaced the glass lens of his camera with ice, most of it gathered from melting glaciers.

During a recent walk-through tour of the exhibition, Duke describes an “obsessive” fascination with glaciers.

“Glacial ice’s structure is unique because it’s constantly being compressed,” he says, “which forces out air bubbles and makes the ice unusually clear.”

Curious to know what it would be like to replace a human gaze with a glacial one, Duke headed to Svalbard, an Arctic Norwegian archipelago where some of the planet’s fastest-rising temperatures have been recorded. Here, he set up an insulated walk-in tent, which he transformed into a giant camera. Duke gathered ice from the surrounding tundra and shaped it into lenses, using molds of his own invention.

“Photography is deeply embedded in a narrative of technological progress,” Duke explains, “but the ice lens isn’t about progress—it’s about shifting perspective.”

In some ways, Duke says, his interest in ice began when he picked up an old Chinese book and came across the story of a third century alchemist who created fire using a ball of ice and reflected sunlight; later, Duke successfully recreated the alchemist’s experiment, resulting in a “union of opposites” that continues to inspire his work today. Glacial Optics might not be directly focused on man’s “technological progress,” according to Duke, but it sure does speak to its ingenuity.

As ice lenses melt, the images they capture become distorted. Duke leads the tour past photographs of sailboats, white-capped waves and a group of huddled human forms. In one composition, we can just make out the blurred contours of a sailing ship, moving unhurriedly through gauzy pink clouds and blue sea. On the opposing wall, black and white photos offer crisper visions of snowy climes. The camera’s narrowed, circular viewpoint feels strangely intimate: the portholed view of an ancient mariner, maybe.

Upon returning to the States, Duke reviewed his Arctic photos and grew concerned that they were too shrouded in mystery, too distant—too indomitable.

“I was taken aback by the romance of the images,” he explains. “I didn’t want them to feel remote or ‘other-worldly.’”

He pauses in front of a forest landscape.

“I wanted what I was photographing to be animate, to have agency—and to speak to the unchecked, cataclysmic impact of human life on Earth,” he adds.

In response, Duke headed to Colorado and New Mexico, where he photographed the aftermath of the Marshall and Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fires, respectively. Duke crafted lenses of local tap water, keeping them as cold as he could in scorching, post-blaze temperatures. Blurred, charred trees seem to huddle together in one image, their branches stark and scarred by flames. Because they are seen through melting lenses, Duke’s trees appear to swirl together, retreating from the viewer’s gaze.

SITE curator Brandee Caoba, who began planning Glacial Optics with Duke in 2021, says the show’s seemingly oppositional entities of ice and fire are united in depicting climate change’s far-reaching impacts.

“Tristan is tenacious,” Caoba says, “and he follows his curiosity and intuition. The photographs in Glacial Optics stand on their own, and can be enjoyed for their beauty, but they also disallow us from dismissing the reality of climate change.”

Towards the end of the tour, Duke stops in front of a black and white image of five vertical, translucent cylinders. These are ice cores, he tells us, extracted from dying glaciers near the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro in the 1970s and ’80s, and currently stored at a research lab in Ohio. Duke says some of earth’s glaciers have been around for millions of years, and act as remarkably accurate time-keepers. Pointing to a dark smudge in the bottom of one of the slim cylinders, he says, “This is a layer of compressed dust that accumulated 4,200 years ago, over a hundred-year period. It lines up with several major earth-changing events, like the drought that was responsible for bringing down Egypt’s Old Kingdom.”

Before the group disperses, someone asks about his future plans. Duke says he’s planning to continue documenting glaciers, and also mentions a new dream.

“Meteorites are fascinating to me,” he notes,” and I’d really love to be able to study them in depth.” Fire, ice, and now cosmic dust: For Tristan Duke, it’s all inexorably, ephemerally related.

Photographs of Antarctica taken by Tristan Duke using an ice lens

October 2024

Western Fashion: From Vintage to Super Vintage.

Shop Western Treasures at Santa Fe Vintage/This City Different vintage shop is an international destination for lovers of Western cool.

By Iris Fitzpatrick /photos by Tira Howard

TWENTY MINUTES SOUTH of the contemporary Western fashion juggernaut that is Santa Fe Plaza, an unassuming warehouse off Airport Road holds 4,200 square feet of some of the finest, coolest, and most hard-to-find vintage Western wear in the world. Step into Santa Fe Vintage, and the store unfolds into cavernous rooms holding racks of Western-yoked shirts from H Bar C and Pendleton, leaning stacks of silver belly Western hats, and big barrels of tissue-soft bandanas.

After original founder Scott Corey passed away in 2020, longtime collaborator and buying partner Teo Griscom and her husband, Josh Kalmus, took over with a mission to continue Corey’s passion for vintage clothing and authentic Western wear. “As soon as I could drive, I would hit at least one thrift store a day,” says Griscom, who grew up in Galisteo during the 1990s. “There were still so many amazing pieces to find.”

Thrifting has become more competitive, but gems at Santa Fe Vintage are everywhere. “Santa Fe’s fashion scene has very unique Western and Native influences,” Griscom says. “[Because we source] from the fascinating and eclectic people who have lived here over the years, you’re bound to find amazing things.”

Nolan Hall wears a Chimayó jacket among Santa Fe Vintage’s large selection of denim.

Take the denim section. Perfectly weathered pairs of Levi’s form towering stacks, but each are thoughtfully organized and folded with reverence. If you’re lucky, you might unearth a pair in your size sporting a tiny orange flag on the backside—a short-lived midcentury branding move to distinguish fashion-forward styles from more utilitarian ones. Lesser known but fabulously named denim brands such as Copper King, Dee Cee, and Buckaroo figure alongside Lee and Wrangler.

Not sure where to start? Griscom has an impressive knowledge of historic clothing and how to style it. “Every closet should have a good pair of OG-107s,” she says, referring to Korean War–era cotton army pants named for their color: Olive Green shade 7. “They look great paired with a worn-in Wrangler denim shirt.” As a wardrobe stylist for 20 years, Griscom also regularly rents out historical items to New Mexico–based movie productions and photo shoots. “Styling is intense work, but I have a whole warehouse to pick from,” she says.

Wardrobe stylist Teo Griscom, with 20 years of experience, supplies historical items to New Mexico film and photo productions from her extensive warehouse collection.

Santa Fe Vintage also serves an international clientele. “A friend of mine introduced me to buying and selling to the Japanese,” says Griscom, who has tapped into this vibrant consumer base to form relationships with other vintage devotees.

In addition to vintage Western wear’s aesthetic appeal and historical value, Griscom says, it offers us a chance to mindfully fill our wardrobes with timeless pieces. “My personal stance on owning less involves learning what looks good on you first,” she says, “and then getting your staples like old Levi’s and cool T-shirts.” Over time, add to your collection with unique statement pieces like Chimayó jackets.

Another amazing thing to love about vintage? “Its quality far surpasses the fast fashion of today,” she says. “From the fabric to the sewing, it was all so superior to today’s standards.”

Read more: The future of Chimayó weaving is in good hands.

Double Take’s collection includes an impressive array of bolo ties.

TREASURE HUNT

Santa Fe’s vintage Western-wear scene is unmatched. Be sure to check out Double Take and Kowboyz, both on South Guadalupe Street. A respected boot destination, Kowboyz also carries ranch shirts and cowboy hats. Double Take is the town’s best-known consignment store, with where-did-you-get-that offerings like snakeskin hats, outsize concho belts, and bolos with huge chunks of turquoise. Betterday Vintage is a laid-back outpost specializing in funky clothes and old vinyl records, all curated with tender care. Hit up the weekend mercado at El Museo Cultural to browse vintage vendors who know their stuff.

Emily Trujillo’s Modern Take on Weaving/The future of Chimayó weaving is in good hands.

Sep. 25, 2024

By Iris Fitzpatrick

Photo: Emily Trujillo helps a student at Centinela Traditional Arts. Photograph by Emily Trujillo.

AT 31 YEARS OLD, Emily Trujillo is the heir apparent to a textile legacy that began eight generations ago, when Mexico-born Diego Trujillo settled in the village of Chimayó in the mid-1600s. Over the centuries, the family became masters of weaving blankets, jackets, vests, and other textiles in the Río Grande style, characterized by Mexican Saltillo and Vallero designs, including chevroned stripes and serrated diamonds. “For my family, weaving isn’t just a way to make a living,” Trujillo says. “It is part of who we are, and it’s an important aspect of our culture.”

Although tradition figures prominently at the family’s Chimayó studio and storefront, Centinela Traditional Arts, Trujillo understands that for their artistic legacy to survive, they must appeal to new generations of buyers. At her Albuquerque-based home studio, she often eschews symmetry in favor of creativity. “Improv is a constant part of my family’s weaving process and always has been,” she says. “If you rely too much on geometry and perfection, one little mistake can throw off your entire design.” Classic Río Grande design elements like central diamonds, for instance, hover UFO-like across a composition, surrounded by thunderbirds, hourglasses, and even grazing sheep. In her modern practice, Trujillo also deviates from the red, black, and white palette of her ancestors with shades like a vivid neon cerise that she calls “screaming pink.”

Because attracting a new era of textile artists is also critical, her family incorporates teaching into their practice, offering classes through regional schools and community centers. Their biggest hurdle is finding dedicated labor, a challenge Trujillo attributes to the “lack of instant gratification” that goes along with a practice as labor- and time-intensive as weaving.

She hopes targeted programs, like a recent partnership with Western apparel company Ariat, may help generate fresh excitement. “In exchange for licensing designs created by artists here in New Mexico, Ariat supplied us with a $50,000 grant to train weavers and even guarantee them jobs,” Trujillo explains. “The future of Chimayó weaving really depends on getting people interested in it.”

9-30-24: Pie Projects

By Iris Fitzpatrick for the Santa Fe Reporter

Santa Fe drivers looking to get from Agua Fría Street to Cerrillos Road in a hurry have used Baca Street for decades. It’s narrow, even by City Different standards, and winds through mature residential neighborhoods before crossing Potencia Street near Larragoite Park; from here, Baca becomes more noticeably bohemian with its super casual vibe complemented by artist studios and galleries that crop up as Baca’s intersection with Cerrillos Road approaches.

This super-chill area, the Baca Arts District, includes Baca Street offshoots Flagman Way and Shoofly Street. Here, among other elements, you’ll find sleek condos, Turner-Carroll Gallery’s contempo offshoot CONTAINER and top-notch Argentinian/Armenian/Italian restaurant Cafecito and parking that’s typically plentiful. I’m here to meet with Alina Borsa, who, along with her husband Devendra Contractor, operates Pie Projects, a contemporary art gallery that opened in 2021.

Contractor is the founding principal at Devendra Narayan Contractor & Associates, the firm responsible for building most of Santa Fe’s Railyard arts district (several miles east of Baca), and recently, the Vladem Contemporary satellite wing of the New Mexico Museum of Art.

I’m visiting Shoofly Street on an overcast morning, and pull up to Pie Projects’ curb just as the day’s scant sunlight threatens to disappear completely; the sizable brunch crowd at Cafecito, Pie’s neighbor, is unbothered, its patrons happy to be in a place as mellow-feeling as Shoofly Street.

“We get lots of casual foot traffic,” says Borsa, who greets me at Pie’s entrance. “but lately, more people are visiting us on purpose.”

Borsa was born and raised in Switzerland, and first came to Santa Fe in 2008; she never intended to stay permanently, but here she happily remains, 16 years later.

“Contemporary art keeps us in the present moment,” Borsa tells me as we tour the gallery.

Borsa’s interest in art is one she shares with Contractor, whose firm constructed the mixed-use building that houses Pie Projects in 2019. (The compound, as Borsa calls it, includes a downstairs unit occupied by DNCA, as well as a pair of residential units upstairs). The gallerists’ commitment to supporting currently working artists is evidenced in a pair of unexpectedly complementary exhibitions that open Saturday.

Contemporary Miniatures presents demure offerings from artists James Bristol, Caroline Liu, Catherine Eaton Skinner and Cedra Wood.

“Artists love making big paintings, but they take up a lot of space here,” Borsa says, gesturing around the 1,500-square foot gallery. “Smaller works can be just as powerful.”

We walk toward a tiny lake scene by Wood, a Las Vegas, New Mexico-based multi-disciplinary artist who was a 2020 participant in the prestigious Roswell Artist-in-Residency Program. From a distance, Wood’s black and white landscape looks like a photograph, but her medium is graphite, which is expertly applied in hyperrealistic strokes that gleam metallically in especially shaded parts. At the center of the composition is a round of bread, scooped out to hold a flickering candle. Beyond, pointy treetops appear gripped by strong wind. Borsa studies me with a smile.

“It’s a little ominous, isn’t it?” she asks.

The gallery’s other group show, Variations, features painters Richard Hogan and Sam Scott, plus sculptor Paul Bloch. Borsa and Contractor’s representation of well-established and highly respected artists like these is the result of focusing on relationship-building.

“We were introduced to Sam Scott and we offered him a show, which led us to represent him,” says Borsa, “Sam Scott introduced us to Dana and Eugene Newmann, and Jerry West was introduced to us by Meridel Rubenstein.”

Many members of the group still create and actively exhibit art well into their 80s.

“The artists of this generation like to meet at our openings,” says Borsa, “they all know each other and support each other.”

As she’s talking, I notice a trio of small collages by Larry Bell, another regional artist whose sphere of creative influence extends beyond the Southwest.

“We don’t represent Larry, but he is a close friend of lots of artists we do represent,” Borsa explains.

Bell’s work is formally carried by Hauser and Wirth, an ultra-blue-chip gallery that happily sends artwork from Los Angeles to Santa Fe for Bell to include in Pie Projects shows.

Outside, the rain changes from a sizzle to a drumbeat, its attendant wind stirring a hedge of bamboo. I turn to look at a geometric abstract painting by Lua Brice, an artist with whom I’m unfamiliar. Borsa follows my gaze.

“Isn’t this incredible?” she says, her eyes sparkling with genuine excitement. “We found out about Lua through C. Alex Clark, who installed our lighting.”

Clark, a gallery lighting specialist, holographic artist and longtime fixture of the Santa Fe art scene, says “I showed Alina some of Lua’s work a while back, and she liked it so much she decided to include it in the show.”

I look back at the mesmerizing painting in front of me and notice a red dot on its accompanying wall label. Clark won’t say who bought it, but does tell me that the buyer was older—and also a local artist. I’m heading for the rain-streaked door when Borsa’s partner Contractor appears.

“The building we’re standing in was originally named Shoofly Pie, so we played off of that,” he says when I ask about the gallery’s namesake. “Pie appeals to people both as a delicious treat, and as a representation of irrationality.”

Clockwise from top: A petite graphite drawing of a grasshopper on a dried salt lake bed by Cedra Wood; A holographic work by Augut Muth; Abstraction by Lua Brice.

8/28/24: Garden Variety

Canyon Road has been evolving for thousands of years—its treasures are abundant and for everyone

by Iris Fitzpatrick / August 28, 2024

Canyon Road might be considered ancient by most Americans, but here in New Mexico, we know better. Sure, it’s hosted galleries for the past half-century, but its reputation as an art hub pales next to the thousands of years it existed as a path used by nearby Pueblo communities. When the Spanish arrived in the first decade of the 1600s, they immediately built an irrigation ditch here to divert precious water from the Santa Fe River. Still later, when the Santa Fe Trail sliced through town in 1821, fortune seekers, outlaws, and missionaries used the path, gradually widening it to accommodate covered wagons and later, Model T Fords.

Across a couple of late August afternoons, I checked out this prehistoric path-turned-gallery zone, exploring a couple dozen or so of the 80-plus businesses on Canyon Road to find a few highlights. In its present iteration, Canyon Road is designed to attract people with enough money to buy flabbergastingly spendy art, but that doesn’t mean curious locals are unwelcome.

“The feeling on this road can be extremely communal,” longtime Canyon Road gallerist Tracy King, who is one of ViVO Contemporary’s nine artist-owners, says, " like a gathering place.”

Events like the buzzy, city-sponsored Canyon Road Summer Walk, next slated for Wednesday, Sept. 4, are heartening to King.

“Community events are great to drive foot traffic,” she explains. “People aren’t necessarily buying art because of them, but that’s OK.”

My first stop is Nuart Gallery (670 Canyon Road, (505) 988-3888), a longstanding contemporary gallery housed in the former Gormley’s, one of several grocers who served rural Canyon Road families in the 1900s. The gallery still retains showy storefront windows, and inside, its creaky wood floors lead you through multitudinous rooms, resplendent with Spanish-Pueblo Revival and Territorial architectural details. The real treasure is just outside the gallery, though, on Gormley Lane. This little shortcut from Canyon Road to Acequia Madre looks prettiest in the early evening, when its brick storehouses and stoic cottonwoods cast dramatic shadows across the well-worn dirt road. Keep strolling to Acequia Madre or loop back to Canyon Road via the gallery-lined Gypsy Alley. Here you’ll find Gypsy Baby, which offers thoughtfully arranged goodies like smirking plush shrimps, insanely chic baby outfits, and droll party supplies, lots of it under $40.

It’s been 250 years since the first recorded residential settlements cropped up along Canyon Road, and some excellent examples of these early homes remain. On the road’s north end is the stately former Borrego House, which was more or less in continual habitation from the time Geronimo Lopez built in the 1700s until 1992, when the building was purchased and transformed into fine-dining establishment Geronimo (724 Canyon Road, (505) 982-1500). Yes, the prices are high and the vibes can be stuffy, but the old home’s austere beauty is worth a gander—especially if you’re lucky enough to score a spot at the famously tiny bar inside.

Are twelve-foot-tall metal wind sculptures high art? No. Are they cool to look at? Hell, yes. You’re amiss, even curmudgeonly, to roll your eyes at the prospect of walking around Canyon Road simply to look at big sculptures. There are dozens of dazzling outdoor spaces to explore, and I found those at Legacy Gallery (225 Canyon Road, (505) 986-9833), El Zaguán (545 Canyon Road, (505) 983-2567), and Zaplin Lampert (651 Canyon Road, (505) 982-6100) especially enchanting. If you’re looking for even more green space, walk north to Patrick Smith Park (1010-1098 E Alameda St.) and enjoy hilly expanses of grass and the best dog-watching in the whole city.

By the roaring 20s, artists like Will Shuster and Gerald Cassidy descended on Canyon Road, living and working in converted studios and developing a collector base through exhibitions hosted at the Museum of New Mexico. Get a taste of what inspired this wave of creative transplants at the curatorially excellent Matthews Gallery (659 Canyon Road, (505) 992-2882), which specializes in secondary market paintings from hallowed American modernists like Arthur Dove and Janet Lippincott.

Near the start of the Canyon, you’ll find Project Tibet (403 Canyon Road, (505) 982-3002), a nonprofit retail and community space that’s welcomed visitors with lush gardens, plentiful parking and feel-good shopping since 1980. Project Tibet’s generous emerald gardens are home to dozens of peaceful carved Buddha statues and shaded benches, making it an ideal resting spot for tired walkers. Inside the store, Project Tibet offers T-shirts emblazoned with Hindu gods, colorful animal mobiles, wool hats and even yak adoption opportunities. Much of the merchandise is under $30, and your money goes to a good cause.

My personal favorite thing about Canyon Road is the Santa Fe River Trail, which is actually a block away from the Road, off of Delgado Street. Heading down Delgado and away from Canyon, turn right onto the dirt road just before East Alameda to access a narrow, mostly flat path that feels worlds away from Canyon Road’s commercial pursuits. Tall grasses and wildflowers border this river path, which culminates in an enchanting rock waterfall.

8/14/24: Artist as Hunter

Tony, Tony, Burning Bright

In his latest creative incarnation, Tony Abeyta showcases the best of the best in modern American art

By Iris Fitzpatrick for the Santa Fe Reporter

It’s late summer in Santa Fe, and Downtown Subscription’s parking lot is jam-packed with expensive and beautiful foreign cars, opulent under an August sun whose light this morning bathes everything in a secretive pre-fall glow. I’m thinking about the way things look because I’m meeting with Tony Abeyta, whose angular landscapes are also lush; craggy hills softened by thick stripes of rain and dervishing blue-gray wind. Abeyta works in a range of media, but it’s these landscapes—rich with magpies, gods and forest fires—that launched him into art stardom.

Today, Abeyta says, he’s going for a “kinda gentrified” look with the fit: soft and spotless white tee, khaki shorts, white Adidas ankle socks and scuffed black Louis Vuitton loafers. He blushes when I tell him he’s a Santa Fe fashion icon, but he knows I mean it. Abeyta the sartorialist is one of his many moods. There’s also the son, the brother, the father, the fisherman; the flea-market-fiend and the Scorpio. Increasingly, Abeyta is known as art historian and expert appraiser, roles informed by a lifelong passion for collecting and trading beautiful things.

“I was always surrounded by people making art,” he says of growing up Diné in Gallup, New Mexico, a sort of hub for Zuni, Hopi and Navajo people for many hundreds of years.

“I’ve always loved the treasure hunt aspect of collecting,” Abeyta continues by way of an explanation of his latest project, a show of 70 objects from his personal collection called Hunter, on view through late September at newbie nonprofit International Center for the Arts, or ICA. The show is objectively stunning, thanks in large part to native Santa Fean and ICA founder Chiara Geovando, who describes Abeyta as a “formidable dealer with an almost encyclopedic memory.”

Espresso in hand, Abeyta explains that the Diné were traditionally hunters and gatherers following prey and the seasons, moving with a confidence he understands.

“I never collect art because someone tells me it’s good,” Abeyta explains. “Taste is arbitrary, so I rely on my own.”

A hunter’s hunger does not exclude his predilection for certain sustenance over others, but the list of things Abeyta loves is much longer than things he doesn’t—the latter category including The Clash (which he can take or leave), Native American arrowheads (“just never really been my thing”) and over-the-top PCism, which he says is often “prohibitive and cumbersome.” Abeyta is wild, however, about contemporary Native artists like Jeffrey Gibson (Mississippi Band of Choctaw and Cherokee) and Virgil Ortiz (Cochiti Pueblo), and also loves Black American painters Kerry James Marshall, whom he calls his favorite American painter, and Kehinde Wiley.

Abeyta has finished his first cortado and is onto his second.

“I’m more of a Ferris Bueller than a Jack Kerouac,” he says thoughtfully, and I believe him.

This tendency toward cheekiness is evidenced in works found in Hunter, like a banana made of black beads and encased in a yellow vinyl peel by Nick Cave, a pair of gold-painted moccasins by TK and a framed hot dog by Caddo and Kiowa painter TC Cannon. Abeyta loves collecting work that’s more pointed in examining the ongoing ignorance that’s plagued white understandings of Native people, and lots of the best, most knock-your-socks off examples of this are made by artists who also happen to be friends of close friends: This includes currently practicing artists like dynamo Cochiti Pueblo potter Diego Romero, as well as dearly departed art lions Fritz Scholder (La Jolla Band of Luiseño), Otellie Pasiyava (Hopi) and Charles Loloma (Hopi). As hunters go, Abeyta is well-experienced, and selects the best and most meaningful objects for his nourishment.

“I tell people to look for work that holds an intrinsic mystery,” he says. “Be uncomfortable, seek out challenging work.”

Abeyta’s existence is informed by listening to music.

“It’s safe to say my music taste is almost entirely thanks to women,” he says, with real earnestness. “Girlfriends in the ′90s made the best mixtapes.”

He adores De La Soul and the Beastie Boys, but also keeps his eyes and ears peeled for more obscure recordings. A small cross-section of Abeyta’s beloved album collection is displayed at ICA, all by Native American musicians.

Years ago, Abeyta lived in Taos and befriended the minimalist painter Agnes Martin, who “loved kids and Italians,” he says, and who became his semi-regular Tuesday lunch companion for years.

“She never once showed any interest in explaining why she painted the way she did,” Abeyta says.

In Hunter, Martin and Abeyta’s mutual affection is commemorated with a framed lithograph in the former’s characteristically meticulous style and tenderly signed, “For my friend Tony.” Another contemporaneous Taoseño was neighbor Dennis Hopper, who impressed Abeyta with his kind demeanor. Hopper’s son Henry gave Abeyta a beat-up script of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. It’s one of many, many items showing at ICA that’s worth the visit.

I watch as Abeyta leaves the coffee shop and moves into the sunshine, pausing for just a flash to revel in a juicy tangle of Mexican roses and fat sunflowers growing right up to the curb with petals washed in the same light as tiny dogs and fussy gallery directors and ancient, smiling men; all of it food for a hungry hunter.

Hunter: Selections From the Personal Collections of Tony Abeyta: 10 am-5 pm Thursday-Saturday through Sept. 28. Free. 906 S St. Francis Drive, icasantafe.org

8/4/24: An assignment on San Ildefonso

Image: A fine dusting of ash covers a batch of freshly fired pottery.

Fire Keepers

Maria Martinez’s kin keep the fire burning on San Ildefonso Pueblo

Image: A fine dusting of ash covers a batch of freshly fired black-on-black pottery. (Iris Fitzpatrick)

By Iris Fitzpatrick for The Santa Fe Reporter August 07, 2024

Imagine a village surrounded by black rock cliffs and sloping green hills, dotted with apricot trees and playing children. Sunlight filters through the leaves of the towering Big Tree, an ancient cottonwood positioned like a sentinel along the northern end of the community’s central plaza. Notice a woman and a man sitting in the shade of the Big Tree. She is polishing a pot, filling the air with steady whish-whish-whishing sounds that will last until the vessel’s surface is as smooth as the skin of an unbroken lake. The man is working even more quietly, painting feathers and serpents and thunderheads onto the polished pots with a brush he dips in milky red clay slip.

Seventeen-year-old Maria Martinez (1887-1980) was already a sought-after potter when she married husband Julian (1879–1943) in 1904. It was a heady time for the San Ildefonso natives: Within a decade or so of the railroad’s arrival in Northern New Mexico in 1880, archaeologists came here to dig up burial grounds belonging to prehistoric Mimbres people. These sites brimmed with remarkably well-preserved bowls, their bone-white bellies painted with geometric designs and fantastic creatures. Seeing the Mimbres pottery up close, either at dig sites or in Santa Fe curio shops, electrified Maria and Julian, says their great-grandson, the potter Marvin Martinez.

Marvin Martinez, Maria Martinez’s great-grandson, puts the final touches on the family’s fire pit base. Red cedar is chosen as kindling for its abundance and its tolerance of extra-hot temperatures. (Iris fitzpatrick)

I’ve been invited to the Martinez home to see firing techniques pioneered by Maria and Julian and rigorously adhered to by their descendants. When I pull up, Marvin and his son Manuel are lining an outdoor pit with cedar before topping it with a rack of red clay pots destined for the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts’ 102nd Indian Market later this month. I ask about the ring of feathers circling many of the pots.

“They’re eagle feathers,” Marvin tells me as we watch plumes of gray smoke rise from the fire pit. “Eagles can fly two miles high, so we say they can carry messages from us all the way up to heaven.”

Marvin’s wife Frances, who grew up on neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, appears from the house with cold bottled water. Like her husband, she was taught to thank the earth when removing hunks of it for clay, to measure earth with coffee cans, and to watch a fire closely.

“People always want to know how long the firing takes, and I’m like, ‘I don’t know, an hour? Two hours?’” Frances says with a laugh. “We go by how the way things feel, not by minutes and hours.”

Smoke from the fire pit has become darker and thicker and, emboldened by gusty wind, it stings the nostrils and eyes. It’s time to smother the fire, Marvin tells Manuel, and they shovel horse manure onto the smoldering pit, starving the fire of oxygen and trapping the scorching smoke within, turning red pots into black ones.

I move indoors, where Frances is making fresh clay. She shakes sifted earth onto a tarp covering the kitchen floor, shaping it into a shallow crater. Today is special, because two of her grandkids, Autumn, 9, and Nathaniel, 4, are here to help. Nathaniel solemnly nods his head in agreement whenever grandma talks, underscoring her words by murmuring, “yeah, yeah.” I am charmed by his earnestness, his need to make sure people listen to his grandmother as keenly as he does.

“I don’t have a plan when I start making a pot,” Frances notes while gently pouring water into the crater that’s becoming clay. “You have to let the clay tell you what it wants to be.”

“Yeah!” Nathaniel shouts, and we laugh.

Marvin and Frances were both raised by their grandparents, and they place a premium on the knowledge imparted to them by their elders.

“A lot of kids don’t want to hang around older people,” Marvin says. “But I was always right behind Adam and Santana. They taught me that the work we do is important.”

Every wall in the Martinez home is hung with family photographs of Maria, she and Julian’s oldest son Adam (1904-2000) and his wife Santana (1909-2002).

“Our family trusted us to continue their work,” Frances continues. “We love to see them and remember them.”

Outside, Manuel is gingerly lifting the rack of pots off the fire pit, where they have safely passed through firing. As I prepare to leave, Frances gets wistful. When she was young, she says, all the kids played “rezball” in the arroyos until dark.

“They don’t do that anymore,” she says.

I follow her gaze to State Road 30, the main road for Santa Clara and San Ildefonso communities. This road has become a thoroughfare for northbound Los Alamos commuters trying to avoid Highway 284. The traffic, Frances tells me, moves too fast or else inches along at a snail’s pace, periodically erupting with horns, loud music and, occasionally, tossed trash. It’s pleasantly quiet today, though—a gift for a happy family whose pitch-black pots carry messages on eagle wings or via winding serpents as conjured and cared for by new generations of San Ildefonso ancestors.

SWAIA Indian Market: 8 am-5 pm Saturday, Sept. 17 and Sunday, Sept. 18. Free. Santa Fe Plaza, 63 Lincoln Ave., swaia.org

Detail of an Avanyu or feathered water serpent design--the most prominent imagery used by Martinez potters (credit: stock image)

Four-year-old Nathaniel, great-great-great-grandson of Maria and Julian Martinez, surveys harvested earth ready to be ground into clay at his family’s property on San Ildefonso Pueblo.

7/29/24: A Market for the People

Spanish Market highlights 2024

I am constantly humbled by the native tongue of all good artists: honesty—honesty with oneself and one’s process. The Nuevo Mexicano artists who carve saints out of juniper and weave sheep’s wool into rugs fit for sultans are honest in their presentation and honest in their devotion to the Catholic iconography of their ancestors.

Bustling with children, quiet tourists, brilliant plaza greenery, and friendly artists, this year’s Spanish Market radiated with honest creative expression. Here are some examples of classic santero carving, including a petite St. Francis holding a little bird, a marvelously expressive St. Joseph, and a turquoise Jesus.

Taoseño Daniel Barela explores new ways of interpreting his forefathers’ art practice. Shown here: St. Joseph foregrounding a richly detailed santuario or Northern New Mexico chapel.

A petite Saint Frances (a beloved Northern NM saint recognizable for his love and veneration of living things'; a crucially important saint to Spanish Catholic culture) Carved by Carlos Santistevan Sr.

Matthew Cordova, a santero from Taos, celebrates beloved Catholic saints in bold color and touching humanity.

Longtime Spanish Market artist Carlos Santistevan enjoys the view from his spot on Palace Avenue. Pictured here, the artist with his Tree of Life.

A special highlight for me during this year’s Spanish Market was meeting three members of the famous Trujillo weaving family. They can trace their lineage all the way back to the mid-1600s, when Miguel Trujillo traded Mexico for rural Northern New Mexico. By the time he arrived, Chimayo was a weaving locale, with big heavy floor looms steadily creating tapestries of intricate geometry and brilliant color.

Patriarch: Irvin Trujillo poses in front of a new work of his, which incorporates daughter Emily’s beloved “screaming pink.” He asked me the difference between a pizza and a weaver; a pizza, he says, can feed a family of four.

Weaving: The silky smoothness of the Trujillo’s tapestries might surprise you. Traditional churro sheep wool is swapped for an ultra-smooth brushed silk Merino in this turquoise stunner.

Mom and daughter: Emily and Lisa Trujillo pose in front of their brilliantly colorful Spanish Market booth on Palace Avenue.

Check them out at https://www.chimayoweavers.com/ where both Lisa and Emily beautifully write about the history of this fascinating, wholly American art form.

11.12.23: The Reluctant Camper turned Enthusiastic Glamper

I headed for southern New Mexico to write about a new kinda campground in beautiful Truth or Consequences. I had a ball on this little jaunt. Article here.

-

Guests have 24/7 access to tin tubs fed by underground springs. Photograph courtesy of Hot Springs Glamp Camp.